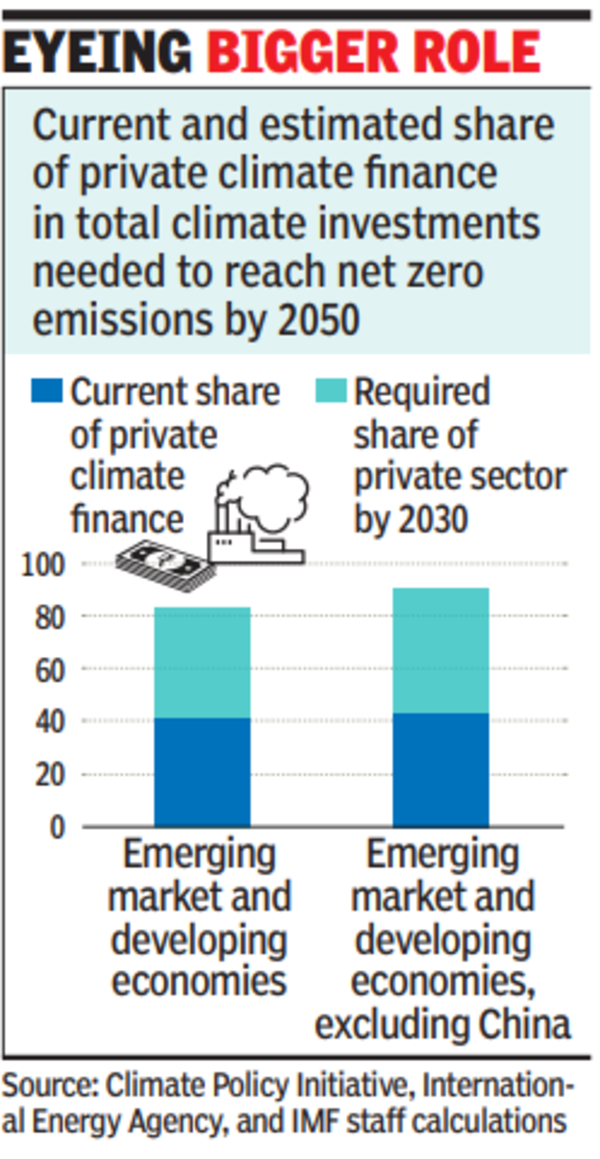

“The private sector will need to supply about 80% of the required investment, and this share rises to 90% when China is excluded,” the global agency said in a post, ahead of the Global Financial Report that is due to be released next week. This would mean that the private sector has to significantly step up its investment from the current level of around 40% (see graphic).

The paper comes at a time when an independent expert group set up by India under its G20 presidency has pointed to the massive amount of capital required to help emerging and developing economies deal with climate change.

The group, co-chaired by Larry Summers and N K Singh, have called for an overhaul of multilateral development banks (MDBs) so that they can leverage own balance sheets and tap into the large pools of private capital to meet the requirements of climate finance. The role of multilateral agencies is seen to be crucial for smaller economies as the larger ones such as India and China have well developed capital markets to tap into private pools of capital.

That’s something that even the IMF paper talks about. “While China and other larger emerging economies have the necessary domestic financial resources, many other countries are missing sufficiently developed financial markets that can deliver large amounts of private finance. Attracting international investors also faces hurdles, as most major emerging market economies and almost all developing countries lack the investment-grade credit ratings that institutional investors often require. And, few investors have experience in these countries and are able to take the higher risk,” it said.

Besides, it has also backed the panel’s suggestions for MDBs and donors to play an important role in supporting blended finance, including through a more extensive use of guarantees.

While seeking changes in policies, the IMF paper points to the absence of focus among most major banks and funds in targeting net-zero climate targets. It said that several investment funds prioritise sustainability but only a small amount flows towards projects that explicitly create a positive climate impact.

“The much larger number of funds that make investment decisions based on environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) factors don’t necessarily focus on climate issues. They typically consider ESG scores in their portfolio allocations, but these aren’t necessarily designed to reflect climate impact… More impact-oriented investment portfolios could be quite different from the popular ESG-oriented ones,” it said, adding that the credit rating parameters often do not recognise the work being done by middle- and low-income countries.